Style of Art Emphasized Straight Lines Precise Drawing Balanced Formalism

In the visual arts, style is a "...distinctive mode which permits the grouping of works into related categories"[1] or "...whatsoever distinctive, and therefore recognizable, way in which an act is performed or an artifact made or ought to be performed and fabricated".[ii] It refers to the visual appearance of a work of art that relates it to other works by the same artist or one from the same period, training, location, "school", art motion or archaeological civilization: "The notion of style has long been the fine art historian's main way of classifying works of art. By manner he selects and shapes the history of art".[3]

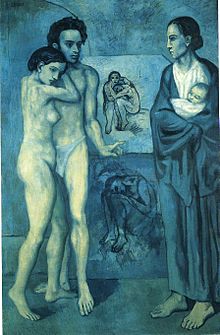

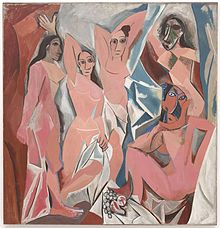

Style is oftentimes divided into the full general fashion of a catamenia, country or cultural group, group of artists or fine art movement, and the individual way of the artist inside that group style. Divisions within both types of styles are often made, such as between "early", "eye" or "late".[4] In some artists, such every bit Picasso for instance, these divisions may exist marked and easy to see; in others, they are more subtle. Style is seen as usually dynamic, in virtually periods always irresolute by a gradual process, though the speed of this varies greatly, from the very irksome evolution in mode typical of prehistoric fine art or Ancient Egyptian art to the rapid changes in Modern art styles. Style often develops in a series of jumps, with relatively sudden changes followed past periods of slower evolution.

After dominating academic word in art history in the 19th and early on 20th centuries, so-chosen "style fine art history" has come up under increasing attack in recent decades, and many art historians now prefer to avert stylistic classifications where they can.[v]

Overview [edit]

Any piece of art is in theory capable of being analysed in terms of fashion; neither periods nor artists can avert having a way, except by complete incompetence,[6] and conversely natural objects or sights cannot be said to take a style, as style simply results from choices fabricated by a maker.[vii] Whether the artist makes a conscious choice of style, or tin identify his own style, hardly matters. Artists in recent developed societies tend to be highly conscious of their own style, arguably over-conscious, whereas for before artists stylistic choices were probably "largely unselfconscious".[8]

Well-nigh stylistic periods are identified and divers later past art historians, just artists may cull to define and proper name their own style. The names of virtually older styles are the invention of art historians and would not have been understood by the practitioners of those styles. Some originated as terms of derision, including Gothic, Baroque, and Rococo.[9] Cubism on the other paw was a conscious identification made past a few artists; the discussion itself seems to have originated with critics rather than painters, but was rapidly accustomed by the artists.

Western fine art, similar that of some other cultures, most notably Chinese fine art, has a marked tendency to revive at intervals "classic" styles from the past.[10] In critical analysis of the visual arts, the fashion of a work of fine art is typically treated as distinct from its iconography, which covers the subject and the content of the work, though for Jas Elsner this distinction is "not, of course, true in any actual example; but it has proved rhetorically extremely useful".[eleven]

History of the concept [edit]

Classical art criticism and the relatively few medieval writings on aesthetics did not greatly develop a concept of style in art, or assay of it,[12] and though Renaissance and Bizarre writers on art are greatly concerned with what we would telephone call mode, they did not develop a coherent theory of it, at least outside compages:

Artistic styles shift with cultural conditions; a self-evident truth to any modern art historian, but an boggling idea in this period [Early on Renaissance and earlier]. Nor is it clear that any such idea was articulated in antiquity... Pliny was attentive to changes in ways of art-making, just he presented such changes as driven by engineering and wealth. Vasari, too, attributes the strangeness and, in his view the deficiencies, of earlier art to lack of technological know-how and cultural sophistication.[thirteen]

Giorgio Vasari set out a hugely influential but much-questioned account of the evolution of style in Italian painting (mainly) from Giotto to his own Mannerist menstruation. He stressed the development of a Florentine style based on disegno or line-based drawing, rather than Venetian colour. With other Renaissance theorists like Leon Battista Alberti he continued classical debates over the all-time balance in fine art between the realistic depiction of nature and idealization of it; this debate was to go on until the 19th century and the appearance of Modernism.[fourteen]

The theorist of Neoclassicism, Johann Joachim Winckelmann, analysed the stylistic changes in Greek classical art in 1764, comparing them closely to the changes in Renaissance art, and "Georg Hegel codified the notion that each historical menses will have a typical style", casting a very long shadow over the study of style.[fifteen] Hegel is oftentimes attributed with the invention of the High german word Zeitgeist, just he never really used the give-and-take, although in Lectures on the Philosophy of History, he uses the phrase der Geist seiner Zeit (the spirit of his time), writing that "no man can surpass his own time, for the spirit of his time is too his own spirit."[16]

Constructing schemes of the menstruum styles of historic art and architecture was a major business concern of 19th century scholars in the new and initially mostly German-speaking field of fine art history, with of import writers on the broad theory of style including Carl Friedrich von Rumohr, Gottfried Semper, and Alois Riegl in his Stilfragen of 1893, with Heinrich Wölfflin and Paul Frankl standing the debate in the 20th century.[17] Paul Jacobsthal and Josef Strzygowski are among the art historians who followed Riegl in proposing grand schemes tracing the transmission of elements of styles beyond keen ranges in time and space. This type of art history is also known as formalism, or the written report of forms or shapes in fine art.[18]

Semper, Wölfflin, and Frankl, and later Ackerman, had backgrounds in the history of architecture, and like many other terms for period styles, "Romanesque" and "Gothic" were initially coined to describe architectural styles, where major changes betwixt styles tin can exist clearer and more like shooting fish in a barrel to ascertain, not to the lowest degree because style in architecture is easier to replicate by following a set of rules than way in figurative art such as painting. Terms originated to draw architectural periods were often subsequently applied to other areas of the visual arts, and then more widely still to music, literature and the full general culture.[19]

In architecture stylistic change frequently follows, and is made possible by, the discovery of new techniques or materials, from the Gothic rib vault to modernistic metal and reinforced concrete construction. A major area of argue in both art history and archæology has been the extent to which stylistic alter in other fields similar painting or pottery is likewise a response to new technical possibilities, or has its ain impetus to develop (the kunstwollen of Riegl), or changes in response to social and economic factors affecting patronage and the weather of the artist, equally current thinking tends to emphasize, using less rigid versions of Marxist fine art history.[20]

Although style was well-established equally a central component of art historical assay, seeing information technology as the over-riding factor in art history had fallen out of fashion by World War Ii, as other means of looking at art were developing,[21] also as a reaction confronting the emphasis on mode; for Svetlana Alpers, "the normal invocation of way in art history is a depressing affair indeed".[22] According to James Elkins "In the afterwards 20th century criticisms of manner were aimed at further reducing the Hegelian elements of the concept while retaining it in a form that could exist more easily controlled".[23] Meyer Schapiro, James Ackerman, Ernst Gombrich and George Kubler (The Shape of Fourth dimension: Remarks on the History of Things, 1962) have fabricated notable contributions to the contend, which has too drawn on wider developments in critical theory.[24] In 2010 Jas Elsner put it more strongly: "For virtually the whole of the 20th century, style fine art history has been the indisputable rex of the discipline, only since the revolutions of the seventies and eighties the king has been dead",[25] though his commodity explores means in which "way fine art history" remains alive, and his annotate would hardly be applicable to archeology.

The use of terms such as Counter-Maniera appears to be in pass up, equally impatience with such "manner labels" grows among art historians. In 2000 Marcia B. Hall, a leading art historian of 16th-century Italian painting and mentee of Sydney Joseph Freedberg (1914–1997), who invented the term, was criticised by a reviewer of her Later on Raphael: Painting in Central Italy in the Sixteenth Century for her "fundamental flaw" in continuing to utilize this and other terms, despite an apologetic "Notation on style labels" at the beginning of the book and a hope to keep their employ to a minimum.[26]

A rare contempo attempt to create a theory to explain the process driving changes in artistic mode, rather than merely theories of how to describe and categorize them, is by the behavioural psychologist Colin Martindale, who has proposed an evolutionary theory based on Darwinian principles.[27] However this cannot be said to have gained much support among fine art historians.

Individual fashion [edit]

Traditional art history has also placed cracking emphasis on the individual way, sometimes chosen the signature style,[28] of an creative person: "the notion of personal style—that individuality tin be uniquely expressed not only in the manner an creative person draws, but also in the stylistic quirks of an author'southward writing (for case)— is perhaps an axiom of Western notions of identity".[29] The identification of private styles is especially important in the attribution of works to artists, which is a ascendant cistron in their valuation for the art market, above all for works in the Western tradition since the Renaissance. The identification of individual style in works is "essentially assigned to a group of specialists in the field known every bit connoisseurs",[30] a group who centre in the art trade and museums, often with tensions between them and the community of academic fine art historians.[31]

The exercise of connoisseurship is largely a thing of subjective impressions that are hard to analyse, but besides a thing of knowing details of technique and the "hand" of dissimilar artists. Giovanni Morelli (1816 – 1891) pioneered the systematic study of the scrutiny of diagnostic pocket-sized details that revealed artists' scarcely conscious shorthand and conventions for portraying, for example, ears or hands, in Western quondam principal paintings. His techniques were adopted by Bernard Berenson and others, and have been applied to sculpture and many other types of art, for example past Sir John Beazley to Attic vase painting.[32] Personal techniques can be of import in analysing individual style. Though artists' training was before Modernism essentially imitative, relying on taught technical methods, whether learnt as an apprentice in a workshop or later as a student in an academy, there was ever room for personal variation. The idea of technical "secrets" closely guarded by the master who developed them, is a long-continuing topos in art history from Vasari's probably mythical business relationship of Jan van Eyck to the secretive habits of Georges Seurat.[33]

However the idea of personal mode is certainly not limited to the Western tradition. In Chinese art it is just every bit deeply held, but traditionally regarded as a factor in the appreciation of some types of art, in a higher place all calligraphy and literati painting, but not others, such as Chinese porcelain;[34] a distinction also often seen in the then-called decorative arts in the West. Chinese painting likewise allowed for the expression of political and social views by the creative person a good deal earlier than is normally detected in the Westward.[35] Calligraphy, also regarded as a fine art in the Islamic earth and East Asia, brings a new expanse within the ambit of personal way; the ideal of Western calligraphy tends to exist to suppress individual style, while graphology, which relies upon it, regards itself as a scientific discipline.

The painter Edward Edwards said in his Anecdotes of Painters (1808): "Mr. Gainsborough'due south manner of penciling was and then peculiar to himself, that his work needed no signature".[36] Examples of strongly private styles include: the Cubist art of Pablo Picasso, the Pop Art style[37] of Andy Warhol, Impressionist style of Vincent Van Gogh, Drip Painting past Jackson Pollock

Manner [edit]

"Manner" is a related term, often used for what is in effect a sub-sectionalisation of a manner, perhaps focused on item points of style or technique.[38] While many elements of period style can be reduced to characteristic forms or shapes, that tin can fairly be represented in elementary line-drawn diagrams, "style" is more often used to mean the overall fashion and temper of a work, especially complex works such as paintings, that cannot so easily be subject to precise analysis. It is a somewhat outdated term in academic fine art history, avoided because it is imprecise. When used it is ofttimes in the context of imitations of the individual style of an creative person, and it is one of the hierarchy of discreet or diplomatic terms used in the fine art trade for the relationship betwixt a work for sale and that of a well-known artist, with "Fashion of Rembrandt" suggesting a distanced relationship betwixt the style of the work and Rembrandt's ain style. The "Caption of Cataloguing Practice" of the auctioneers Christie's' explains that "Mode of..." in their auction catalogues ways "In our stance a work executed in the artist'due south mode but of a later engagement".[39] Mannerism, derived from the Italian maniera ("manner") is a specific phase of the full general Renaissance style, only "style" can be used very widely.

Fashion in archaeology [edit]

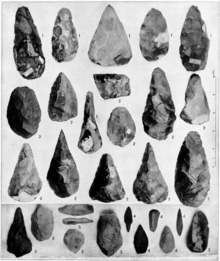

In archaeology, despite modern techniques like radiocarbon dating, period or cultural style remains a crucial tool in the identification and dating non just of works of art but all classes of archaeological artefact, including purely functional ones (ignoring the question of whether purely functional artefacts exist).[40] The identification of individual styles of artists or artisans has also been proposed in some cases even for remote periods such as the Ice Age art of the European Upper Paleolithic.[41]

As in art history, formal analysis of the morphology (shape) of individual artefacts is the starting point. This is used to construct typologies for dissimilar types of artefacts, and by the technique of seriation a relative dating based on mode for a site or grouping of sites is achieved where scientific absolute dating techniques cannot be used, in particular where but stone, ceramic or metallic artefacts or remains are available, which is oft the example.[42] Sherds of pottery are oft very numerous in sites from many cultures and periods, and fifty-fifty small pieces may be confidently dated by their style. In contrast to recent trends in academic fine art history, the succession of schools of archaeological theory in the terminal century, from culture-historical archaeology to processual archaeology and finally the ascension of post-processual archæology in recent decades has not significantly reduced the importance of the study of style in archaeology, as a basis for classifying objects before further interpretation.[43]

Stylization [edit]

Stylization and stylized (or stylisation and stylised in (non-Oxford) British English language, respectively) have a more specific significant, referring to visual depictions that employ simplified ways of representing objects or scenes that do not try a full, precise and accurate representation of their visual appearance (mimesis or "realistic"), preferring an attractive or expressive overall depiction. More technically, it has been defined as "the decorative generalization of figures and objects by means of various conventional techniques, including the simplification of line, form, and relationships of space and color",[44] and observed that "[south]tylized art reduces visual perception to constructs of pattern in line, surface elaboration and flattened infinite".[45]

Ancient, traditional, and modern art, as well as pop forms such as cartoons or animation very ofttimes use stylized representations, so for case The Simpsons use highly stylized depictions, as does traditional African art. The 2 Picasso paintings illustrated at the top of this page show a movement to a more stylized representation of the homo figure inside the painter's style,[46] and the Uffington White Horse is an example of a highly stylized prehistoric depiction of a horse. Motifs in the decorative arts such every bit the palmette or arabesque are often highly stylized versions of the parts of plants.

Even in art that is in full general attempting mimesis or "realism", a degree of stylization is very often constitute in details, and especially figures or other features at a small scale, such as people or copse etc. in the distant groundwork even of a large work. But this is not stylization intended to be noticed past the viewer, except on shut examination.[47] Drawings, modelli, and other sketches not intended as finished works for sale volition also very often stylize.

"Stylized" may mean the adoption of any way in any context, and in American English is often used for the typographic style of names, equally in "AT&T is also stylized as ATT and at&t": this is a specific usage that seems to have escaped dictionaries, although it is a small extension of existing other senses of the give-and-take.[ citation needed ]

Computer identification [edit]

In a 2012 experiment at Lawrence Technological University in Michigan, a computer analysed approximately 1,000 paintings from 34 well-known artists using a especially adult algorithm and placed them in similar style categories to human art historians.[48] The analysis involved the sampling of more than 4,000 visual features per work of art.[48] [49]

See also [edit]

- Artistic rendering

- Composition (visual arts)

- Mise en scène

Notes [edit]

- ^ Fernie, Eric. Art History and its Methods: A critical anthology. London: Phaidon, 1995, p. 361. ISBN 978-0-7148-2991-three

- ^ Gombrich, 150

- ^ George Kubler summarizing the view of Meyer Schapiro (with whom he disagrees), quoted by Alpers in Lang, 138

- ^ Elkins, due south. i

- ^ Elkins, southward. 2; Kubler in Lang, 163–164; Alpers in Lang, 137–138; 161

- ^ George Kubler goes farther "No human being acts escape style", Kubler in Lang, 167; Two, 3 in his list; Elkins, s. 2

- ^ Lang, 177–178

- ^ Elsner, 106–107, 107 quoted

- ^ Gombrich, 131; Honour & Fleming, 13–14; Elkins, s. 2

- ^ Honour & Fleming, 13

- ^ Elsner, 107–108, 108 quoted

- ^ classical authors did leave a considerable and subtle body of analysis of manner in literature, especially rhetoric; run into Gombrich, 130–131

- ^ Nagel and Woods, 92

- ^ See Blunt throughout, with in detail pp. 14–22 on Alberti, 28–34 on Leonardo, 61–64 on Michelangelo, 89–95 and 98–100 on Vasari

- ^ Elkins, s. 2; Preziosi, 115–117; Gombrich, 136

- ^ Glenn Alexander Magee (2011), "Zeitgeist", The Hegel Dictionary, Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 262, ISBN9781847065919

- ^ Elkins, s. 2, 3; Rawson, 24

- ^ Rawson, 24

- ^ Gombrich, 129; Elsner, 104

- ^ Gombrich, 131–136; Elkins, s. 2; Rawson, 24–25

- ^ Kubler in Lang, 163

- ^ Alpers in Lang, 137

- ^ Elkins, s. 2 (quoted); see also Gombrich, 135–136

- ^ Elkins, south. 2; analysed past Kubler in Lang, 164–165

- ^ Elsner, 98

- ^ Spud, 324

- ^ Summarized in his commodity "Evolution of Ancient Art: Trends in the Style of Greek Vases and Egyptian Painting", Visual Arts Enquiry, Vol. 16, No. 1(31) (Spring 1990), pp. 31–47, University of Illinois Press, JSTOR

- ^ Suffern, Erika (2013). "Review of The Signature Style of Frans Hals: Painting, Subjectivity, and the Market in Early Modernity". Renaissance Quarterly. 66 (1): 212–214. doi:10.1086/670435. ISSN 0034-4338.

- ^ Elsner, 103

- ^ Alpers in Lang, 139, a situation she sees as problematic

- ^ Exemplified in grumbling by Grosvenor; Crane, 214–216

- ^ Elsner, 103; Dictionary of Fine art Historians: "Giovanni Morelli"

- ^ Gotlieb, throughout; 469–475 on Vasari and van Eyck; 469 on Seurat.

- ^ Rawson, 92–102; 111–119

- ^ Rawson, 27

- ^ https://museumsandcollections.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/2942274/13_Ritchie_Gainsboroughs-signature-22.pdf[ bare URL PDF ]

- ^ "Pop art | Characteristics, Definition, Style, Move, Types, Artists, Paintings, Prints, Examples, Lichtenstein, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved 2021-10-13 .

- ^ "What Is Poetry?", "Petronius Arbiter", The Art World, Vol. 3, No. 6 (Mar., 1918), pp. 506–511, JSTOR

- ^ Christie's "Caption of Cataloguing Practice" (after lot listings). "Style" is not used for paintings etc., merely for European porcelain they give the case:"A plate in the Worcester style" means "In our opinion, a copy or imitation of pieces made in the named mill, place or region". For examples, this painting, sold by Bonhams in 2011 as "Manner of Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn", is now attributed in their notes to "an anonymous eighteenth-century follower of Rembrandt". This instance sold by Christie's fetched just £750 in 2010.

- ^ Kubler, George (1962). The Shape of Fourth dimension : Remarks on the History of Things. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.Kubler, p. 14: "human products e'er incorporate both utility and art in varying mixtures, and no object is conceivable without the admixture of both"; meet also Alpers in Lang, 140

- ^ Bahn & Vertut, 89

- ^ Thermoluminescence dating can exist used for much ceramic material, and the developing method of Rehydroxylation dating may get widely used.

- ^ Review by Mary Ann Levine of The Uses of Manner in Archeology, edited by Margaret Conkey and Christine Hastorf (see further reading), pp. 779–780, American Antiquity, Vol. 58, No. 4 (Oct., 1993), Gild for American Archaeology, JSTOR

- ^ "Stylization" in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 1979, online at The Gratis Lexicon

- ^ Clark, Willene B., A Medieval Volume of Beasts: The Second-Family Bestiary, Commentary, Art, Text And Translation, p. 54, 2006, Boydell Press, ISBN 0851156827, 9780851156828, google books

- ^ Encounter Elsner, 107 on Picasso as the paradigm of "the supremely cocky-conscious poseur in whatsoever style y'all similar".

- ^ Holloway, John, The Slumber of Apollo: Reflections on Recent Art, Literature, Linguistic communication and the Individual Consciousness, p. 30, 1983, Cambridge Academy Press, ISBN 0521248043, 9780521248044, google books

- ^ a b Suzanne Tracy (ed.), "Computers Lucifer Humans in Understanding Art", Scientific Computing , retrieved November ii, 2012 This is a summary of an article appearing in the ACM Journal on Calculating and Cultural Heritage; the original article was not bachelor at the time of this citation'southward insertion; citation for original publication follows: Shamir, Lior, and Jane A. Tarakhovsky. "Computer analysis of art." Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage (JOCCH) five.two (2012): vii.

- ^ Run across also Gombrich, 140, commenting in 1968 that no such assay was viable at that time.

References [edit]

- "Alpers in Lang": Alpers, Svetlana, "Way is What You Make it", in The Concept of Style, ed. Berel Lang, (Ithaca: Cornell Academy Press, 1987), 137–162, google books.

- Bahn, Paul G. and Vertut, Jean, Journeying Through the Ice Age, University of California Press, 1997, ISBN 0520213068, 9780520213067, google books

- Edgeless Anthony, Creative Theory in Italian republic, 1450–1600, 1940 (refs to 1985 edn), OUP, ISBN 0198810504

- Crane, Susan A. ed, Museums and Memory, Cultural Sitings, 2000, Stanford University Press, ISBN 0804735646, 9780804735643, google books

- Elkins, James, "Fashion" in Grove Fine art Online, Oxford Fine art Online, Oxford Academy Press, accessed March 6, 2013, subscriber link

- Elsner, Jas, "Fashion" in Critical Terms for Art History, Nelson, Robert Southward. and Shiff, Richard, 2nd Edn. 2010, University of Chicago Printing, ISBN 0226571696, 9780226571690, google books

- Gombrich, Eastward. "Style" (1968), orig. International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, ed. D. 50. Sills, 15 (New York, 1968), reprinted in Preziosi, D. (ed.) The Art of Art History: A Critical Album (see below), whose page numbers are used.

- Gotlieb, Marc, "The Painter'due south Secret: Invention and Rivalry from Vasari to Balzac", The Fine art Bulletin, Vol. 84, No. 3 (Sep., 2002), pp. 469–490, JSTOR

- Grosvenor, Bendor, "On connoisseurship", commodity in Fine Fine art Connoisseur, 2011?, now on "art History News" website

- Award, Hugh & John Fleming. A Globe History of Fine art. seventh edition. London: Laurence King Publishing, 2009, ISBN 9781856695848

- "Kubler in Lang": Kubler, George, Towards a Reductive Theory of Style, in Lang

- Lang, Berel (ed.), The Concept of Style, 1987, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, ISBN 0801494397, 9780801494390, google books; includes essays past Alpers and Kubler

- Irish potato, Caroline P., Review of: After Raphael: Painting in Key Italy in the Sixteenth Century by Marcia B. Hall, The Catholic Historical Review, Vol. 86, No. 2 (Apr., 2000), pp. 323–324, Cosmic University of America Press, JSTOR

- Nagel, Alexander, and Forest, Christopher S., Anachronic Renaissance, 2020, Zone Books, MIT Press, ISBN 9781942130345, google books

- Preziosi, D. (ed.) The Art of Art History: A Critical Anthology, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998, ISBN 9780714829913

- Rawson, Jessica, Chinese Ornament: The lotus and the dragon, 1984, British Museum Publications, ISBN 0714114316

Further reading [edit]

- Conkey, Margaret Westward., Hastorf, Christine Anne (eds.), The Uses of Style in Archaeology, 1990, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, Review by Charity Chase Coggins in Journal of Field Archaeology,1992), from JSTOR

- Davis, W. Replications: Archaeology, Fine art History, Psychoanalysis. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Country University Press, 1996. (Chapter on "Way and History in Art History", pp. 171–198.) ISBN 0-271-01524-one

- Panofsky, Erwin. 3 Essays on Way. Cambridge, Mass. The MIT Press, 1995. ISBN 0-262-16151-6

- Schapiro, Meyer, "Fashion", in Theory and Philosophy of Art: Style, Creative person, and Society, New York: Georg Braziller, 1995), 51–102

- Sher, Yakov A.; "On the Sources of the Scythic Animal Style", Arctic Anthropology, Vol. 25, No. 2 (1988), pp. 47–60; University of Wisconsin Printing, JSTOR; pp. 50–51 discuss the difficulty of capturing way in words.

- Siefkes, Martin, Arielli, Emanuele, The Aesthetics and Multimodality of Style, 2018, New York, Peter Lang, ISBN 9783631739426

- Watson, William, Style in the Arts of People's republic of china, 1974, Penguin, ISBN 0140218637

- Wölfflin, Heinrich, Principles of Fine art History. The Problem of the Development of Manner in Afterward Fine art, Translated from 7th High german Edition (1929) into English by One thousand D Hottinger, Dover Publications New York, 1950 and many reprints

- See also the lists at Elsner, 108–109 and Elkins

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Style_(visual_arts)